Introduction

When hardware manufacturers design CPU architectures, for the sake of compatibility and interoperability, they typically choose a general-purpose ISA (Instruction Set Architecture) such as x86, AArch64, or RISC-V. Aside from common metrics like power efficiency and transistor density, one way they tend to compete with one another or differentiate their hardware offerings is by bolstering these base capabilities with hardware-accelerated fast paths carved into silicon to support common applications that would ordinarily require many general-purpose instructions to execute. One such example is Intel’s SHA extensions.

If we think of Solana as a computer, we also have a “CPU”. It’s called the SVM (Solana Virtual Machine), and it’s based upon a general-purpose ISA called BPF (Berkeley Packet Filter). As a VM, however, rather than explicitly prescribing an underlying physical architecture, the SVM instead ingests BPF bytecode and JIT (Just-In-Time) compiles it for execution in whatever underlying physical architecture you choose – in our current universe, that’s x86.

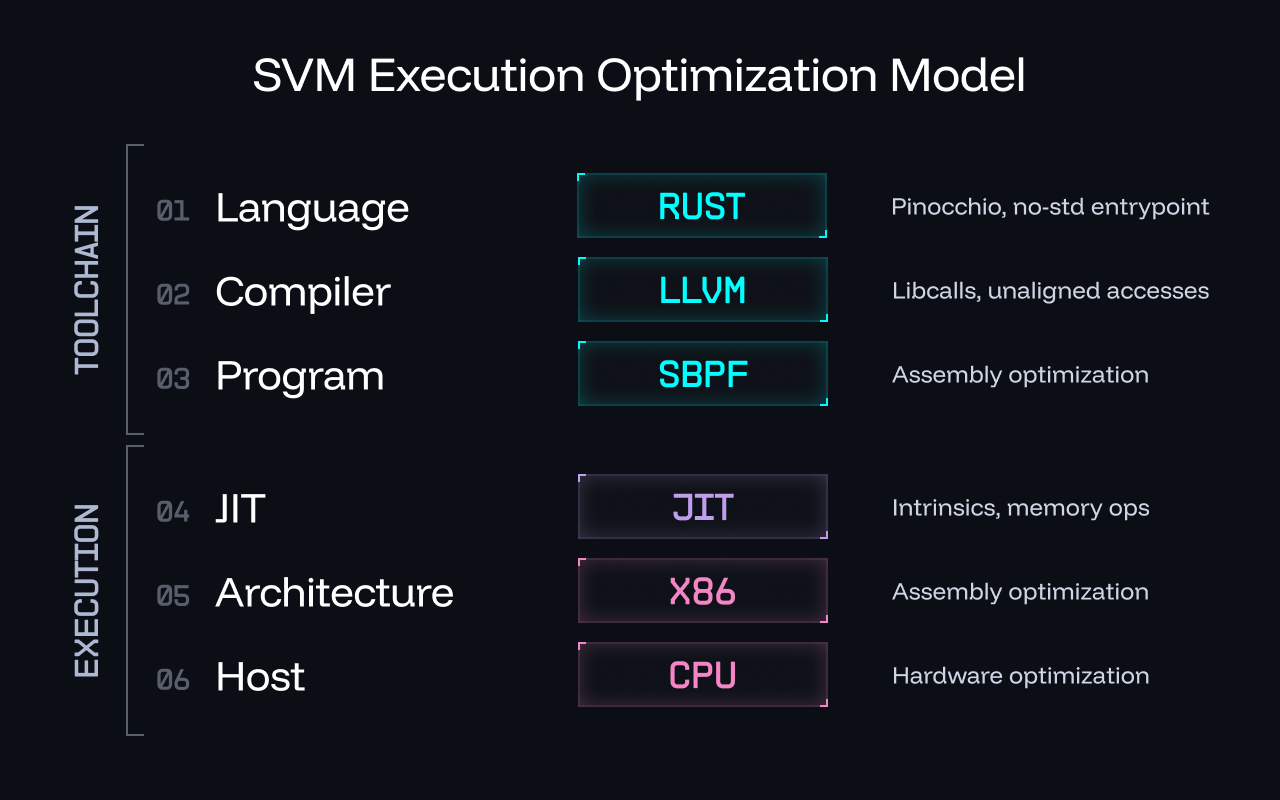

When it comes to optimizing SVM execution, historically, we have primarily focussed upon improving our Rust libraries. With the introduction of Blueshift’s sBPF toolchain, assembly optimizations have also come into the spotlight, highlighting various performance gains that the compiler and our libraries have left on the table. Beyond this, however, there are actually several more layers at which we can unlock additional performance gains to further optimize program execution. See the SVM Execution Optimization Model below:

When optimized with the aforementioned methods, BPF already boasts excellent performance in executing a large variety of general-purpose tasks. As the BPF ISA does not map 1:1 to x86 however, there will always be some inherent inefficiencies in JIT compilation. One way to overcome these limitations is to break the ISA by introducing additional instructions. The major downside to this approach is that all related BPF tooling, such as debuggers, disassemblers and compilers, also break with it. Instead, in this article, we’ll explore a novel approach we call “JIT intrinsics” that enables us to unlock the unrealized performance capabilities of the underlying host architecture of the SVM by tapping into the x86 instruction set at the JIT layer, all while maintaining BPF ISA compatability.

What is an intrinsic?

Perhaps you’re familiar with the term “intrinsic” but are wondering what it means in this context. In the context of programming, compilers, and CPU architecture, intrinsics can be simply understood as:

Low-level functions used by compilers to bridge high-level code to built-in (intrinsic!), platform-specific hardware capabilities, providing a significant performance boost for commonly performed tasks.

Sound familiar? That’s because intrinsics are the glue that enables compilers to give programming languages the capability to unlock those fast paths CPU manufacturers carve into their silicon, speeding up your code execution on capable platforms by physically forcing those electrons to take a shortcut to their final destination.

What is a JIT intrinsic?

Consider what this means in the context of Solana. We have a fake computer called the SVM. Our JIT is a compiler. We have physical access to x86 in our underlying silicon. We can do the same thing those CPU manufacturers do by empowering our JIT compiler to unlock hardware-accelerated variants of semantically identical functions – essentially extending our existing instruction set with the capabilities of its underlying architecture, but without breaking compatibility with the BPF ISA.

What about syscalls?

At first glance, JIT intrinsics do resemble syscalls. While both provide access to functionality beyond the base BPF instruction set, the key difference lies in how they are executed, and the associated performance costs of each approach.

Syscalls

Syscalls execute as follows:

-

BPF program invokes a syscall instruction

-

Execution exits out of JIT-compiled code

-

Control transfers to the runtime’s syscall handler

-

Syscall implementation runs

-

Control returns to JIT-compiled code

This transition incurs significant overhead from saving and restoring state, crossing trust boundaries, and dispatching through the syscall handler.

JIT Intrinsics

By contrast, JIT intrinsics:

-

Are recognized as regular instructions during JIT compilation

-

Are lowered directly to optimal x86 instruction sequences

-

Execute inline at runtime without exiting the JIT

This enables zero-abstraction access to native hardware capabilities directly within the runtime without breaking the BPF ISA.

How do we add instructions without breaking ISA?

When we look at our JIT, we essentially see one giant match statement that maps instructions like:

BPF instruction -> x86 instruction(s)

One such instruction in the BPF ISA is the CALL_IMM instruction. This instruction is used to invoke static syscalls in the case that its src register is set to r0, or internal function calls in the case that its src register is set to r1. What makes this extremely powerful is that we have the ability in our JIT to take CALL_IMM instructions, check their imm value for some reserved i32 value, and if it matches, map this instruction to some x86 equivalent before entering static syscall resolution.

In this way, we are able to unlock direct access to instructions in the underlying x86 architecture that are more performant than their BPF ISA counterparts.

How does this improve performance?

One really great example of a potential candidate for boosting performance is u64 wide multiplication. In the case of every single CPAMM (Constant Product Automated Market Maker) ever, one of the most common functions we perform is calculating the invariant formula: k = x * y. In Solana, this requires taking in two u64 operands to calculate a u128 (wide) result, gracefully handling u64 integer overflow in the upper 64 bits of the u128 in the case of a large invariant.

In Rust, this would look something like:

fn calculate_invariant(x: u64, y: u64) -> u128 { x as u128 * y as u128 }

In x86-64, this would be handled in a single unsigned 64-bit wide multiplication instruction:

RDX:RAX = RAX * reg

In our BPF ISA, however, because there is no such thing as a u64 wide multiplication instruction, to implement this in pure BPF instructions, we are forced to burn tens of CUs on schoolbook-style multiplication, and when JITted into x86, this balloons out into even more instructions. This is definitely not ideal, and leaves us with only a few options:

- Accept the performance overhead of the ISA

- Fork the compiler and break ISA compatibility by adding new instructions to sBPF

- Leverage existing architecture to unlock x86 interop with a JIT intrinsic

Mapping eBPF to x86

In our JIT, we introduce a new variant of CALL_IMM which mimics a regular static syscall, however rather than having the overhead of invoking an actual syscall, it is instead resolved in the JIT before syscall resolution as a part of the same giant match statement mapping all of our BPF instructions to their x86 assembly counterparts. It would look something like this:

match insn.opc { ebpf::CALL_IMM => { // Check for JIT intrinsics if insn.src == 0 { match insn.imm { // u64 wide multiplication ebpf::SOL_U64_WIDE_MUL_IMM => { let r0 = REGISTER_MAP[0]; // RAX - result low (and multiply operand) let r1 = REGISTER_MAP[1]; // RSI - first operand / result high let r2 = REGISTER_MAP[2]; // RDX - second operand self.emit_ins(X86Instruction::mov(OperandSize::S64, r1, r0)); // RAX = r1 self.emit_ins(X86Instruction::alu_immediate(OperandSize::S64, 0xf7, 4, r2, 0, None)); // MUL r2 self.emit_ins(X86Instruction::mov(OperandSize::S64, r2, r1)); // r1 = RDX (result_hi) }, ... } } }, ... }

How do we use this in Rust?

Static syscalls follow a well-defined calling convention in both the Solana runtime and Rust/LLVM. As such, a JIT intrinsic can be exposed to Rust in exactly the same way without needing any cumbersome compiler changes. From the Rust side, this appears as a thin unsafe wrapper around a defined symbol pointing to an immediate value equal to its Murmur3 hash; in this case:

murmur3(sol_u64_wide_mul) -> 0x61BAE2E8

Thus we can define our JIT intrinsic like so:

#[inline(always)] pub fn u64_wide_mul(a: u64, b: u64) -> u128 { let mut result = core::mem::MaybeUninit::<u128>::uninit(); let sol_u64_wide_mul: unsafe extern "C" fn( result: *mut u128, a: u64, b: u64, ) -> u64 = unsafe { core::mem::transmute(0x61BAE2E8usize) }; // SAFETY: `sol_u64_wide_mul` is a runtime-provided JIT intrinsic // with a stable ABI and guaranteed initialization of `result`. unsafe { sol_u64_wide_mul(result.as_mut_ptr(), a, b); result.assume_init() } }

Now that we have defined our new JIT intrinsic, we can invoke it in the same way as any other syscall:

fn calculate_invariant(x: u64, y: u64) -> u128 { u64_wide_mul(x, y) }

Conclusion

JIT intrinsics provide a pragmatic, low-risk path for future-proofing the Solana runtime, allowing it to evolve in step with advances in hardware and computing architectures. By enabling the runtime to recognize and optimize common instruction patterns, performance improvements naturally accrue as compilers adopt more efficient code generation without requiring disruptive ISA changes or breaking existing BPF tooling.

Over time, a carefully curated set of JIT intrinsics can deliver most of the benefits of an extended ISA while remaining fully backwards-compatible. This approach allows the SVM to transparently exploit new CPU features and map high-level intent, such as u64 wide multiplication, directly onto efficient, semantically identical x86 instructions, improving execution speed while preserving long-term stability.

Want to see how we take this to the next level by vertically integrating a JIT intrinsic into Rust without forking the compiler by leveraging library calls? Check out our next article Accelerating u128 Math with Libcalls and JIT Intrinsics!